A Tribute to Women in Medical History

Women have historically always been responsible for “firsts” in medicine. They doctored their children at first signs of the sniffles. They delivered babies for family and neighbors. They grew herbs to treat ailments and stitched wounds. They assured their family’s health by toiling dawn to dusk growing, preserving, cooking and serving food.

Women have contributed to medicine in all those ordinary ways, but these women’s contributions to medicine have been extraordinary. Their research and commitment led to dramatic shifts in medicine—from assessing babies at birth to understanding the transitions of Alzheimer’s before death.

Rosalind Franklin – Molecular Biologist – Pioneer DNA Research

Although the 1962 Nobel Prize for the double-helix model of DNA went to scientists James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins, it was Rosalind Franklin’s work that helped secure them the award. Rosalind Franklin decided at age 15 that she wanted to become a scientist. She attended one of the only London girls’ schools that offered courses in physics and chemistry. Despite her father’s initial protests, she ultimately earned her doctorate in physical chemistry from Cambridge in 1945.

Following Cambridge, Franklin headed to France to study X-ray diffraction techniques before returning to London to work in a lab along-side Wilkins on separate DNA studies. It has been suggested that one of Franklin’s crystallographic portraits of DNA, shown to Watson by Wilkins, was the spark Watson needed to solve the problem of DNA. His study was rushed to press in Nature with Franklin’s work appearing only as a supporting article. Despite the obvious controversy of who discovered what first, Franklin’s research and photos played a certain role in our understanding of DNA.

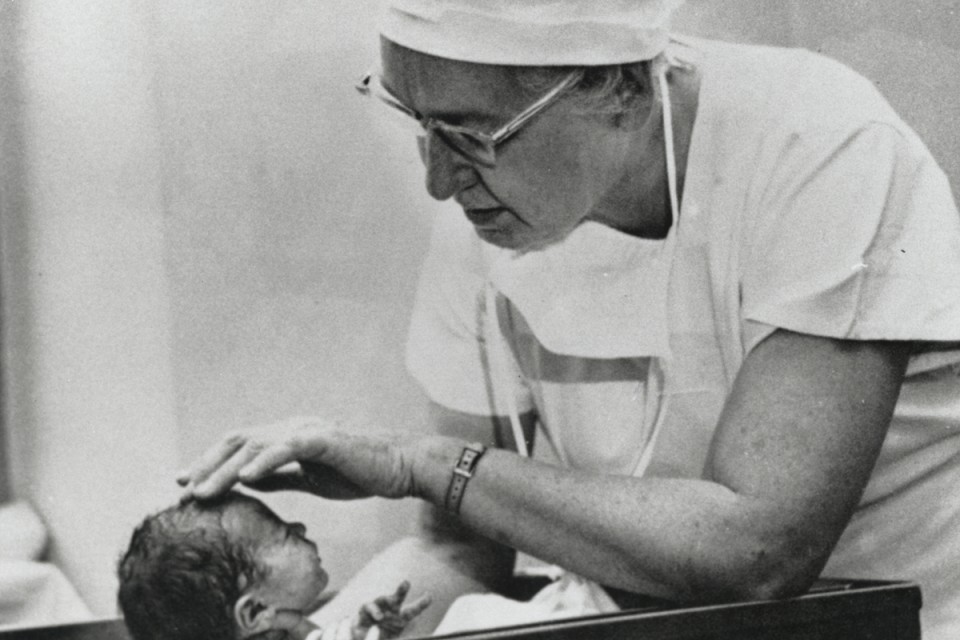

Virginia Apgar, M.D. – Surgeon – Created Apgar Score for Newborns

The first woman to be named a full professor at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Dr. Virginia Apgar’s name is better recognized by women who have given birth. Early in her career, Apgar trained as a surgeon but was encouraged by department head, Dr. Alan Whipple, to study anesthesia as a way to further the surgical field.

At the time, nurses administered anesthesia, and it was not until 1949 when anesthesiology had become a recognized medical profession, that Columbia University made Apgar a full professor in the academic department of anesthesia research. Apgar studied obstetrical anesthesia, and it was during this research that she developed the Apgar Score for measuring an infant’s transition to life outside the womb.

The Apgar Score measures heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex response, and color and assigns a score of 0, 1, or 2 points in each area. The total points equal baby’s Apgar Score.

Rebecca Lee Crumpler, M.D. – Physician – First African American Female Medical Doctor in U.S.

Dr. Crumpler graduated in 1864 from New England Female Medical College, the first African American woman to do so. She quickly left Boston at the end of the Civil War in 1965 for Richmond, Virginia, where she treated former slaves who would otherwise not have access to medical care. In 1883, Crumpler published a book–again a first being one of the first written by an African American—titled Book of Medical Discourses. Her book features medical advice for women and children garnered during her years operating a medical clinic for women and children. There are no authenticated photos of Dr. Crumpler, and the little known about her career is derived from what she shared in her book.

Patricia S. Goldman-Rakic, Ph.D. – Neuroscientist – Pioneer of Brain & Memory Function

Dr. Goldman-Rakic was the first researcher to chart the frontal lobe of the brain, the area that governs insight, personality, reasoning, and other cognitive functions. Her work led to better understanding of brain and memory, and schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Goldman-Rakic’s study of the short-term or “working” memory in the brain and her discovery that the loss of dopamine affects memory, changed how doctors viewed schizophrenia and how they assess and treat other mental illnesses. Additionally, her research into the effects of drugs on the brain generated better understanding of the immediate and long-term effects of various treatments. Sadly, Goldman-Rakic died in 2003 from a head injury sustained when she was hit by a car while walking in Hamden, Connecticut, not far from Yale University where she had conducted much of her research.

Elizabeth Stern, M.D. – Pathologist – Pioneer in Study of Cervical Cancer

Born in Cobalt, Ontario, Canada in 1915, Elizabeth Stern earned her medical degree from University of Toronto in 1939. Stern is a founding mother in cervical cancer research. She pinpointed the 250 stages that transform a healthy cell into a cancer cell—leading to better early detection of cervical cancer. And Stern went on to link herpes simplex virus to cervical cancer and oral contraceptive to cervical dysplasia, which is a precursor to cervical cancer.

In the words of Nobel Prize recipient, biologist Linda B. Buck, “As a woman in science, I sincerely hope that my receiving a Nobel Prize will send a message to young women everywhere that the doors are open to them and that they should follow their dreams.” It is easy to imagine that Goldman-Rakic, Apgar, Crumpler, Franklin and Stern would agree.

Feature image by Elizabeth Wilcox

16 Interviewer Interview Prep

Interviewer Interview Prep Impactful Mentees

Impactful Mentees Benefits of a Mentor

Benefits of a Mentor Advice for First-Time Managers

Advice for First-Time Managers Overcoming the 18-month Itch

Overcoming the 18-month Itch Dressing for Your Style

Dressing for Your Style Interview Style Tips

Interview Style Tips Women's Stocking Stuffers

Women's Stocking Stuffers Gift the Busy Traveler

Gift the Busy Traveler Father’s Day Gift Guide

Father’s Day Gift Guide Airport Layover Activities

Airport Layover Activities Traveling & Eating Healthy

Traveling & Eating Healthy Travel Like a Boss Lady

Travel Like a Boss Lady The Dual California Life

The Dual California Life Gifts for Thanksgiving

Gifts for Thanksgiving Summer Reading List

Summer Reading List Top Leisurely Reads

Top Leisurely Reads New Year, New Books

New Year, New Books Life Lessons from a Sitcom

Life Lessons from a Sitcom Oprah, Amy or Amal?

Oprah, Amy or Amal?