Their Visions Show an Aversion to the Commonplace and a Steadfast Self-Belief

Known for its quirky cartoons, contemporary views on New York City life, and an iconic look that sports, imperturbably, a font popular in the 1920’s, The New Yorker is a publication that manages to be both hallowed and modern, and invariably offers sophisticated content. Co-founded in 1925 by Jane Grant and her first husband Harold Ross, the magazine continues to publish editions on an almost weekly basis (forty-seven per year), available both in print and online.

The New Yorker is not known for its feminist history or editorial angle, so it may surprise some to learn that Jane Grant was a prominent supporter of women’s rights whose professional path was way ahead of its time. Her journalistic milestones included being the first woman reporter for The New York Times and a founding member of the New York Newspaper Women’s Club, which aimed to promote and support women in journalism. She also contributed to the Saturday Evening Post, and in 1921 co-founded a women’s rights organization known as the Lucy Stone League, dedicated to female independence and advocating that women maintain their own identities by keeping their maiden names after marriage.

Below, we pay tribute below to three women artists who have followed in the footsteps of The New Yorker’s co-founder, and exhibited unique, female creative talent, providing cover art, photography and cartoons to the magazine over the last three decades.

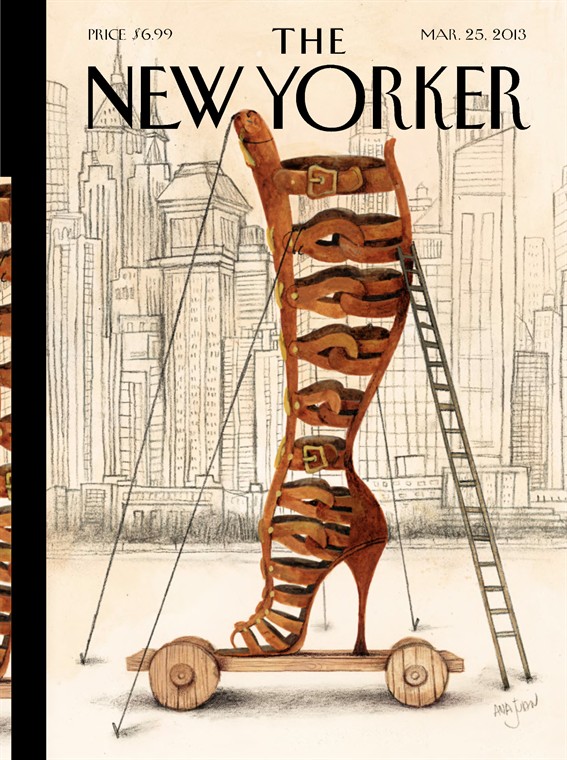

The Foreign-Born Illustrator of Dreamy, Iconic Covers

Ana Juan is a Spanish book illustrator and artist who currently resides in Madrid. She has contributed over twenty covers to The New Yorker since 1995, including the tenth-anniversary cover of the September 11th terrorist attacks, which captures the void left on the Manhattan skyline by the no-longer soaring Twin Towers.

Ana Juan is a Spanish book illustrator and artist who currently resides in Madrid. She has contributed over twenty covers to The New Yorker since 1995, including the tenth-anniversary cover of the September 11th terrorist attacks, which captures the void left on the Manhattan skyline by the no-longer soaring Twin Towers.

Typically made from a mixture of charcoal and acrylic color, her drawings come to life in an eery, dream-like style. On her artistic approach and The New Yorker she states, “The New Yorker has always been very respectful of my style. Working for them, I am keeping my own vision of the world, because in the end, that is what makes an artist different from others. And that distinct vision is just what a magazine like The New Yorker wants — different voices and different views.”

Her life advice: “Be yourself in spite of fashion and tendencies.”

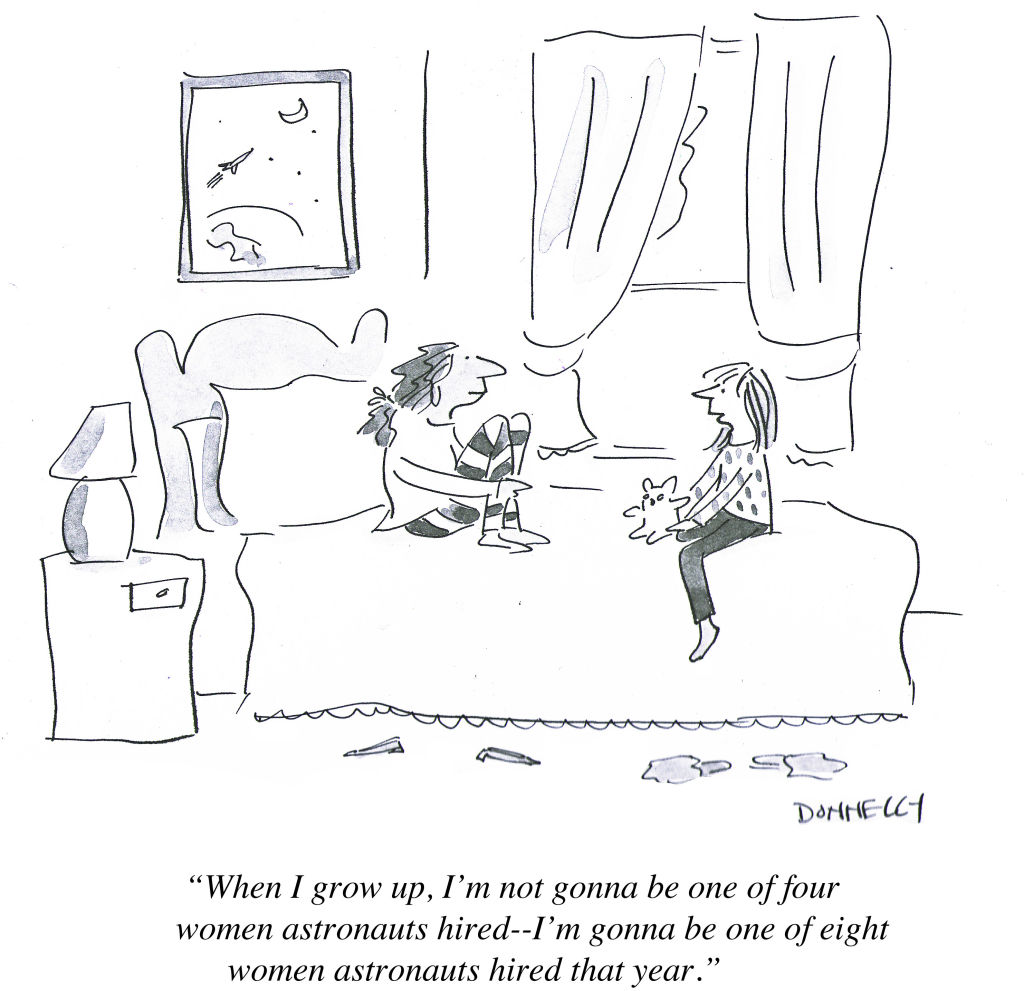

The Feminist, Dry-Humored Cartoonist

Liza Donnelly was a shy, talented artist as a child who found that she could communicate by making people smile with her drawings. After moving to Manhattan post-college and submitting her cartoons to The New Yorker over two years, she finally had one published. In 1982 she started being featured regularly in the magazine, and became one of only three women cartoon contributors at the publication, as well as the youngest at that time.

Liza Donnelly was a shy, talented artist as a child who found that she could communicate by making people smile with her drawings. After moving to Manhattan post-college and submitting her cartoons to The New Yorker over two years, she finally had one published. In 1982 she started being featured regularly in the magazine, and became one of only three women cartoon contributors at the publication, as well as the youngest at that time.

Her cartoons are witty, relatable, and absolutely up-to-the-minute on current news, politics, and pop culture, always making light of otherwise serious situations. What’s her inspiration? “I am inspired by smart and eloquent activists who are thoughtful and do what they espouse, like Jane Goodall [a distinguished English anthropologist known for her work with chimps], Gloria Steinem, Kofi Annan [Former Secretary-General of the U.N.], and Hillary Clinton, to name just a few.”

She also tells us, “My work for The New Yorker covers a lot of different ground—I draw cartoons that can be silly, political or feminist. I think that one of the challenges with my work is how “to draw about feminism” in such a way as to make it of interest to a wide audience. I want to be able to communicate difficult ideas without turning anyone away, yet I want to be true to beliefs, and strong in my ideas, so it is not always easy! I think cartoons are a perfect way to comment on the politics of being a woman, because that is a daily thing for women. And the politics of being a woman are, to one degree or another, the same for all women around the world. If I can help change difficult situations for women through laughter, I would be so happy.”

Donnelly stays busy cartooning and writing for both The New Yorker and Forbes.com; in addition, she is a Cultural Envoy for the US State Department, a public speaker, and has published fifteen books. Her latest volume, Women on Men, was the only female-authored finalist for the 2014 Thurber Prize for American Humor. She is also currently working on a memoir about her younger years and being at The New Yorker, as well as children’s books, one of which will be published next spring.

Her advice to aspiring cartoonists: “Don’t give up! This business involves a lot of rejection, so you have to stick with it and not be deterred by what others think. And draw a LOT. Write a LOT. Keep putting ideas down on paper. Some of them will be lousy, but others will be good. Practice is important.”

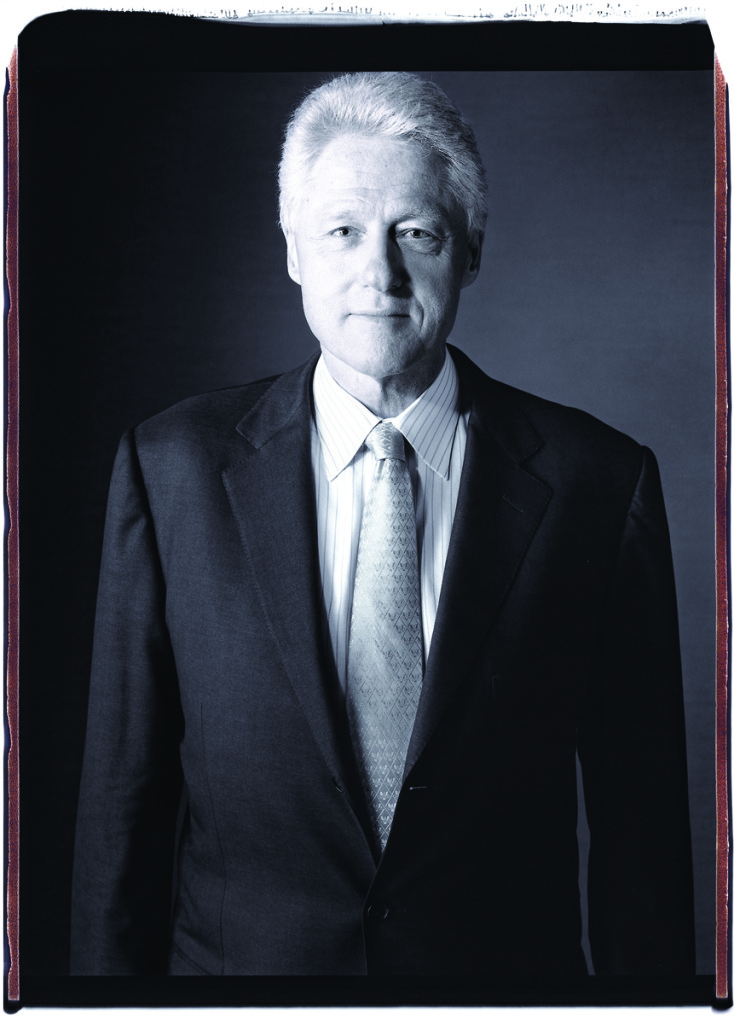

The Hip Creator of Distinctive Photo Imagery

Mary Ellen Mark, a well-known photographer who has lensed portraits of Bill Clinton, Robin Williams, Jim Carrey, Coretta Scott King, and many others, worked for The New Yorker for sixteen years. She covered everything in her role as a photographer: celebrities, New York City events, circuses, street kids, performances, and other, un-classifiable subjects, whose portraits are often inflected with a raw, moody detachment.

Mary Ellen Mark, a well-known photographer who has lensed portraits of Bill Clinton, Robin Williams, Jim Carrey, Coretta Scott King, and many others, worked for The New Yorker for sixteen years. She covered everything in her role as a photographer: celebrities, New York City events, circuses, street kids, performances, and other, un-classifiable subjects, whose portraits are often inflected with a raw, moody detachment.

Of her time at The New Yorker, she says, “Over the years I did many, many pictures for them, and I loved working for them; I loved every minute of it.” She specializes in black-and-white photography, capturing enduring, extraordinary images without any hue. “I think color, when it’s beautifully done, can be wonderful. For myself, I just felt I always saw the world in black and white, and I saw subjects who translated better in black and white. All of the people that I really admired and looked up to in the beginning, their pictures are in black and white.”

It’s been a few years since Mark has photographed for The New Yorker, since then she has been busy with other major projects, such as the book published this past spring called Man and Beast: Photographs from Mexico and India. Also upcoming: a new book of photographs, accompanied with a documentary by her husband, Martin Bell, that captures the last thirty years in the life of a woman nicknamed “Tiny,” whom they first met in the 1980’s. Mark explains: “When I first did a story for LIFE, my assignment was to photograph street kids in Seattle. I met this girl named Tiny; that was her nickname, and she was a thirteen-year old prostitute, very beautiful, and very smart. Over the past thirty years, I’ve done photographs of her, and my husband has filmed her, and so we now have a document of her life. She has ten children now, so it’s not just about her; it’s going to be a journey through those three decades of her life, all about her family and children. It’s been an amazing journey.”

Mark’s staunch advice to others on maintaining a personal vision: “Be who you are, and stay with your convictions. Follow your dreams. That is what is really important — you must fight to do what you believe in, because then you will “have a body of work that represents who you are.” If you want to be an artist, be an artist: if you’re interested in reality, and documenting real life then do that. But be true to yourself; that is what is most important.”

These three women have followed their imaginative impulses, and both changed and documented history. Their success is testament to the power of holding fast to an idiosyncratic, unique vision that, it turns out, others will embrace, and even compensate you well for providing it to the world. The women’s creative zest has also spawned works of art that range from somber to slyly amusing and surreally beautiful.

The common factor to their success, important for anyone in a creative profession, seems to be the idea that artistic instincts must be nurtured, and a steadfast persistence – a kind of inspired tunnel vision — may be necessary to garner huge professional rewards in the end.

TAGS: art photography

Interviewer Interview Prep

Interviewer Interview Prep Impactful Mentees

Impactful Mentees Benefits of a Mentor

Benefits of a Mentor Advice for First-Time Managers

Advice for First-Time Managers Overcoming the 18-month Itch

Overcoming the 18-month Itch Dressing for Your Style

Dressing for Your Style Interview Style Tips

Interview Style Tips Women's Stocking Stuffers

Women's Stocking Stuffers Gift the Busy Traveler

Gift the Busy Traveler Father’s Day Gift Guide

Father’s Day Gift Guide Airport Layover Activities

Airport Layover Activities Traveling & Eating Healthy

Traveling & Eating Healthy Travel Like a Boss Lady

Travel Like a Boss Lady The Dual California Life

The Dual California Life Gifts for Thanksgiving

Gifts for Thanksgiving Summer Reading List

Summer Reading List Top Leisurely Reads

Top Leisurely Reads New Year, New Books

New Year, New Books Life Lessons from a Sitcom

Life Lessons from a Sitcom Oprah, Amy or Amal?

Oprah, Amy or Amal?